Date/Time

Date(s) - 04/22/2022 - 05/14/2022

12:00 am

Location

Buffalo Arts Studio

Categories

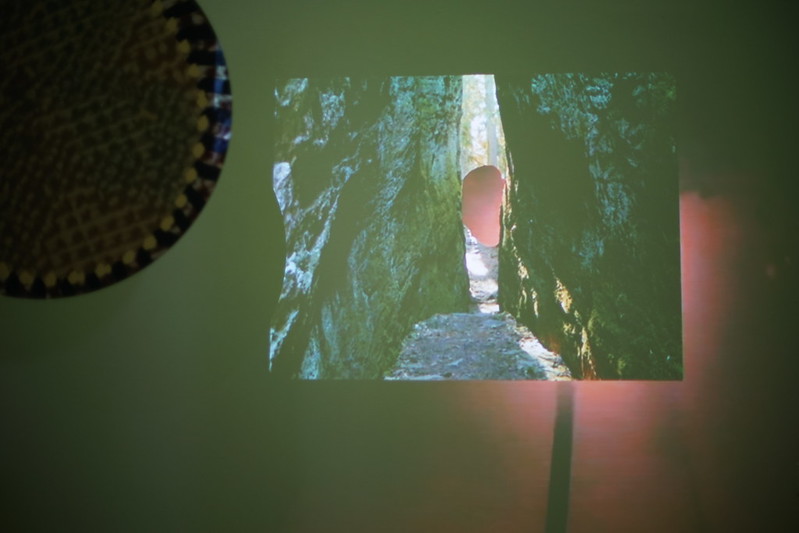

photo by Crystal Z Campbell, video still from VIEWFINDER, 2020; digital video with stereo sound

Opening Reception, Friday, April 22, 2022, 5:00—8:00 pm

Part of M&T Bank 4th Friday @ Tri-Main Center

Crystal Z Campbell’s multidisciplinary practice centers on public secrets, or information known by many, but that is undertold and underspoken. Campbell’s film, VIEWFINDER, was shot entirely in the resort town of Varberg, Sweden and features recent migrants to Sweden. This immersive film installation takes cues from Swedish folktales, gestures, and movements to explore belonging, allyship, and living monuments. If our bodies are archives, what is the currency of place, of movement, of memory?

A conversation between Crystal Z Campbell and curator Shirley T Verrico

STV: You begin many of your projects by searching archives. Does your process begin with a thesis/guiding question or does the question emerge after diving into your research?

CZC: Not long before the COVID-19 pandemic began shifting the landscape of travel, movement, and gesture, I voyaged from my long-term residence in Tulsa, Oklahoma to a small coastal town in Sweden. Varberg was historically known for its sanitorium––a medical retreat to house, care, and isolate people who were affected by an earlier pandemic that could also have complex consequences on the lungs: tuberculosis. After a tuberculosis vaccine was developed, the city gradually began shifting into what it is today, a luxury retreat with the most spas in Sweden.

To make VIEWFINDER, I decided to make use of a residency period in Sweden to shoot a new live action film. Working with archival researchers, they were unable to locate Black people in the regional archive during my time there. I found that fascinating, and decided to make a film centering recent Black migrants to Sweden, that would also be a document of Sweden’s recent history from the eyes of someone clearly outside Sweden. We invented new rituals and narratives in storied lands. In this case, the absence of Black people in these archives is what prompted the work. But I also wanted the work to synthesize everything I was learning about during my time as a tourist. For instance, the film includes some music popular in Swedish midsummer celebrations, but is duplicated and translated by an American musician, and is intentionally, slightly off but close enough to pass as something familiar or nostalgic. There is a proximity to rituals and to customs upon these lands, connected strongly to a national identity, but who do those rituals and customs and land belong to? And what does it mean to belong?

STV: In VIEWFINDER, you film in and around the Varberg Fortress, a former fortification that currently serves as a museum. The interior shots feature an eccentric individual’s collection of books and objects as well. How do you think museums and collections like these actively participate in the absence and erasure you explore in your work? Do you think placing Black people into these spaces amplifies the way(s) Black voices are missing from the stories such places are trying to tell?

CZC: The title of the film, VIEWFINDER references a camera’s viewfinder, or a way to capture something or someone through the gaze. I’ve been thinking a lot about visibility, and the responsibility of looking, of being a witness. I had my own preconceptions about what Sweden would be like, but when I arrived it was clear there was change in this city’s population with more migrants, and that migration was a tense topic. I remember learning about this Swedish law, Allemansrätten, which translates to the Right of Public Access or Freedom to Roam. It’s a law that basically means you have the right to enjoy nature in Sweden, even if it falls on someone’s private property, you can pitch a tent and pick berries, as long as you are respectful of nature and the people residing there. There’s a hospitality in this law that predates recent waves of immigration.

I was working with an elder who translated Swedish folk histories in the archives, and they mentioned this boulder, held by two cliffs, and if the boulder fell, the last person on earth would perish. I traveled to the site in person, and the more I looked at it, the more I wondered if the boulder was being held or if it was holding up the two cliffs. Local legends suggest that should the boulder fall, the last person on earth will perish. I decided to remove the boulder, in the image, to speculate on futurity in relationship to the land. I think of the absence of the boulder as a portal. The photograph became the viewfinder in the film and in some way a question about what it means to project into the future of a place that might not have imagined you in it. The film is a way to think about the geography, lore and the narrative of this particular place, or the narrative the place markets to tourists, versus what other narratives might exist at the same time that remain unseen.

STV: You describe the cloths you photographed as “relics, documents from the region, made by hand, and most likely made by women whose labor was uncredited.” I see these intimate, handmade objects as a counterpoint to the taxidermy hunting trophies and the cannon. How do you see your role as an artist recording these objects and then transforming them into “art” for the gallery space?

CZC: My mother is an immigrant from the Philippines, and I was an expat in the Netherlands for four years and another year in Spain. Coincidentally, my mother worked at a textile factory in her youth. These experiences and questions inform my approach to the texture of making the film and thinking about displacement as a way to choreograph the physical elements of the installation. I’ve often thought my role as an artist is to notice and to pay attention to things. I started off making collages and my work spans different mediums now, but this installation is very much forged from the same principles of collage or even quilt making, of bringing many disparate pieces into a whole. The installation at Buffalo Arts Studio is mediated by large medallions, sounds emanating from disembodied bodies, textiles that nearly disappear, and screens, which are intended to heighten the experience, and make you very aware of your own gaze and your own body in space. It was really important for me to think about how the body is an archive and how our bodies hold our DNA, which is linked to ways of moving through the world guided and shaped by generations before.

The pattern studies of textiles are a residual artifact of my time in Sweden. I’ve been working between the liminal space of what is real and tangible versus what is simulated and digital. The works are a combination of photography and hand painted elements and digital manipulation, and the digital manipulation is intended to simulate painting without the materiality of paint, so there is a loss there, but there is also a quality that can only be done with the digital. I am interested in perception, and space and I think of these pattern studies as a kind of digital trompe-l’oeil.

STV: Your voice narrates the story of Danuta Danielsson, who is memorialized by the statue in the Villa Wäring garden. The photo was originally taken in 1985 and received some notoriety at that time. Based on my research, Danielsson did not want to be named as the woman in the photograph. The statue was made in 2015 and the photo went viral in 2016 during the protests surrounding the US elections. How do you think the 30 years between the original event and the memorial allowed for the myth of The Woman with the Handbag to be constructed?

CZC: I’m still thinking about what you said when referencing one of the videos in the installation, that show a close up of a mouth, and multi-colored teeth in the color palette of the artist, Piet Mondriaan. You mentioned that you were able to google the colors of his teeth and locate his identity, based on that reverse engineering alone. I started thinking about it as a digital forensic exercise, that we might be searchable, if only there was something distinct about us to search for beyond name. But what does it mean to name something, to tie a history to someone? To become known for a single thing? Her image has been shared often by anti-fascist groups and I think there’s such a complex conversation around whether she would want to be named, or would want to be remembered for the single gesture of swatting this Neo-Nazi with her purse, a single gesture that became forever linked to her identity, and her family’s identity. It is a problem inherent to memorializing. There is something to virality that can’t be undone, because it is also part of public memory. In this digital landscape, it’s interesting to think that everyone knows the story or can find it online. But how and when can images from history speak to our present? I also want to consider the limits of performative allyship that peaked in the US and trickled worldwide after George Floyd’s untimely death because of police violence. In the film, there’s a moment where purses are hung on trees in solidarity, but solidarity always requires much more than visibility or the potentially empty gesture.

Film screening:

Crystal Z Campbell, VIEWFINDER

Allan Jamieson, Thunderbeings and the Maid of the Mist

Tuesday, May 3, 2022, 7:00pm, Suite 530 Tri-Main Center

Part of Navigating Identity Exhibition and Workshop Series, which is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

In partnership with Squeaky Wheel Film & Media Art Center.

Thank you to Journey’s End Refugee Services for their generous support of this event.