Date/Time

Date(s) - 07/22/2022 - 09/03/2022

12:00 am

Location

Buffalo Arts Studio

Categories

Opening Reception, Friday July 22, 2022, 5:00—8:00 pm

Part of M&T Bank 4th Friday @ Tri-Main Center

It Is What It Is.

Curatorial Essay by Shirley Verrico

To prepare for his first solo exhibition since 2019, Kyle Butler revisited old sketchbooks, reevaluating ideas he had not realized. For Butler, looking back is just as important as looking ahead, and as a result, a number of ideas continually resurface in his work; parallels between the built environment and human behavior, contrived manners in socialization, and the interplay of competing and cooperating systems. Butler is drawn to what he describes as the “incidental aesthetic,” and his appreciation of found installations and assemblages is an ongoing influence in his work.

“I appreciate the sum total of the worn signage, warped fences, scattered debris, overgrowth, roads that dissipate into grass, and the variety of stones, posts, and other barriers to passage. I regard these environments as a form of municipal expression, a sour visual sentiment brought into being by the unwitting collaboration between residents, governing powers, and infrastructure. While I find these accidental aesthetics amusing, they are also an unflattering indicator of a built environment that is often outright oppressive and a governing system that disregards the well-being of select groups for the sake of capital.”

Although Butler appreciates the accidental, his own work is deeply rooted in contemporary theory and builds on the concept of “necropolitics,” as originally defined by Achille Mbembe. This theory describes how political powers relegate select oppressed populations to death by subjecting them to inhospitable living conditions. Michael Truscello’s Infrastructural Brutalism: Art and the Necropolitics of Infrastructure, focuses on governmental violence such as the destruction of towns and villages for the “progress” of building a dam or the constant polluting of a community to support industry. Truscello recognizes the selective nature of systemic oppression and disregard for environmental health. He also asserts that art can serve as a counter-narrative to the questionable claims of “progress” surrounding infrastructure development and expansion.

Butler has built a subtle, yet powerful counter-narrative with his installation. The video, signage, and sculptural work act as disruptors, pushing against the myth of never-ending forward progress as the result of never-ending construction and development. Big Trash Day serves as a framing device for this body of work, referencing the annual municipal event where, for a brief time, a neighborhood lays out a series of pragmatic sculptures by the roadside to be picked up or picked through.

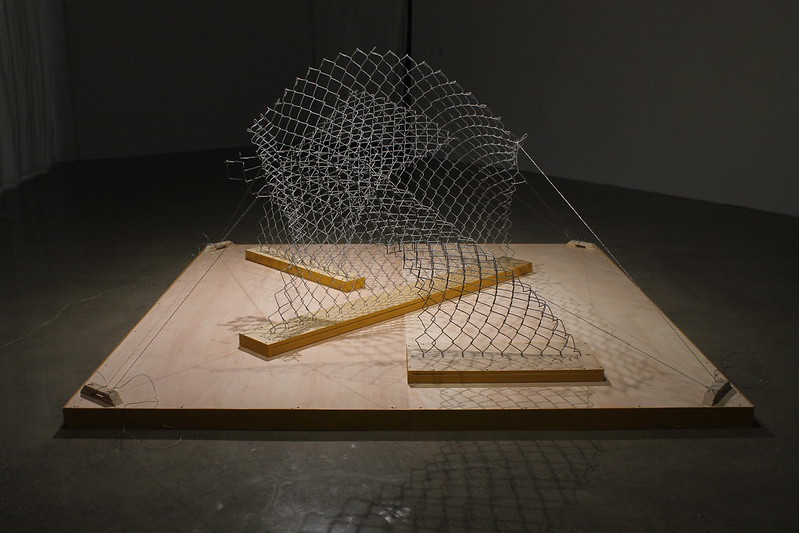

Visitors first see the central sculpture Garbage Façade, which appears to be simply a stack of debris including furniture, boxes, insulation, and black trash bags. The video Garbage Sequence is projected over the trash heap onto a scrap of wood propped up on a pink cinder block. The video includes three stop-action animations produced within the exhibition space. The footage depicts feverishly cycling–but completely illegible–signage, piles of construction debris, undulating fencing, and odd sculptural constructions. Although all of these objects feel familiar in the installation space, none are actually included in the exhibition. They are ghost objects, made and displayed only for the illusion of the projection. The jittery format of the stop motion adds a nearly constant visual disruption through the video itself as well as the flickering light reflected off the screen and onto the main sculpture.

Additionally, there are a series of custom-made road signs that feature ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) depictions of Google Maps images of roadside trash, infrastructural quirks, and piles of urban detritus. In standard ASCII-encoded data, there are unique values for 128 alphabetic, numeric, and special characters and control codes. ASCII was a popular format in the late 1970s and early 1980s for computer bulletin board systems. In Butler’s images, the text connection, along with the size and reflective surface, strengthened the connection to public signage. The ASCII also points to the outdated technology infrastructure often cited for governmental failures. In 2020, many in need were unable to file for unemployment because state governments and unemployment systems used the 60-year-old programming language COBOL. This level of failure was clearly predictable, but somehow state and federal officials feigned surprise.

Moving around the gallery leads to a surprise as well. On the far side of Garbage Façade, the viewer is faced with a structural interior of clean drywall and fresh, gallery-white paint. Unlike the incidental exterior, the interior space is carefully constructed, rising and falling in symmetrical steps. Encountering new drywall, and all of its sterile potential, has become commonplace in this era where it seems everything is under construction. Butler’s juxtaposition of the old and the new, the accidental and the measured, answers Truscello’s call by asking the big questions: is what we find on the interior an improvement, is constant construction and development progress, and is this what we, as a community, really need?

Perhaps the answer to this question can be found in Tongue Mop, the colorful, absurd, and useless object that leans against the wall. It is the only direct reference to the labor embedded in Butler’s process; the individual movement of each object in the animation, the stacking and sorting of the objects in Garbage Façade, and the patching, sanding and painting of the drywall. Butler sees it as just another ingredient in the “idea soup” that is Big Trash Day. I think it is perhaps a bit more. In Butler’s own words, the Tongue Mop answers Big Trash Day’s big question;

“It is what it is.”

Artist Bio:

Kyle Butler is an artist who lives and works in Buffalo, New York. Butler was born and raised in rural Michigan. After completing his BFA at Central Michigan University in 2008, he moved to Buffalo where he earned his MFA in Visual Studies at the University at Buffalo. He is currently Assistant Professor of Fine Art at Villa Maria College.

Butler has exhibited regionally and nationally. He has had solo exhibitions at Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center, the Nina Freudenheim Gallery, and the Buffalo Arts Studio among others. He has been included in group exhibitions at the Albright Knox Art Gallery, the Burchfield Penney Art Center, the Rochester Contemporary Art Center, and Beyond/In Western New York. He was represented by the Nina Freudenheim Gallery until Freudenheim’s passing in 2020. He has been featured in New American Paintings (2010), and his work is in collections including the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Burchfield Penney Art Center and numerous private collections. Butler co-curated the Amid/In WNY exhibition series at Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center (2015/16) and curated and taught at Starlight Studio and Art Gallery, an art center that facilitates adults with developmental disabilities in realizing creative projects.

PDF of the exhibition catalogue is available for download here.

Photos by Creatives Rebuild New York Fellow, Aitina Fareed-Cooke.